| Essay title: | Notes on "Weed Killer" | |

| Author: | Lanka Tattersall, Assistant Curator | |

| Exhibition: | Patrick Staff: Weed Killer | |

| Month and year: | March 2017 |

In 1941 during the Second World War, progesterone and estrogen molecules were first obtained from pregnant mares’ urine.¹ Around the same time, the use of chemotherapy to treat cancer emerged as the unanticipated result of research into the effects of mustard gas as a warfare agent.² These advancements in the biomedical field, along with countless others, have transformed how our bodies are medically and socially treated, in ways both good and ill. Chemotherapy can save lives, though its effects are harrowing. Hormone therapies have helped some transgender individuals develop bodies that align with their gender identity; however, the risk of cancer from these treatments remains unclear. Even as definitions of gender shift, the effects of exclusion and pathologization remain.

The intersection of gender, illness, and contamination is the focal point of the video installation Weed Killer (2017) by Patrick Staff (b. 1987, Bognor Regis, UK; lives in Los Angeles and London). Staff was inspired by artist-writer Catherine Lord’s memoir The Summer of Her Baldness (2004)—a moving and often irreverent account of the author’s experience of cancer. At the heart of Staff’s work is a monologue, adapted from Lord’s book, which reflects upon the chemically induced devastation of chemotherapy. This text is enacted with unrelenting intensity by actress Debra Soshoux, who recites Lord’s description of taking chemotherapy drugs as akin to “mainlining weed killer.” In other words, deeply toxic substances must be ingested, paradoxically, in order to stay alive. Throughout Weed Killer, Staff intertwines notions of affliction and contamination with the demand for survival on one’s own terms.

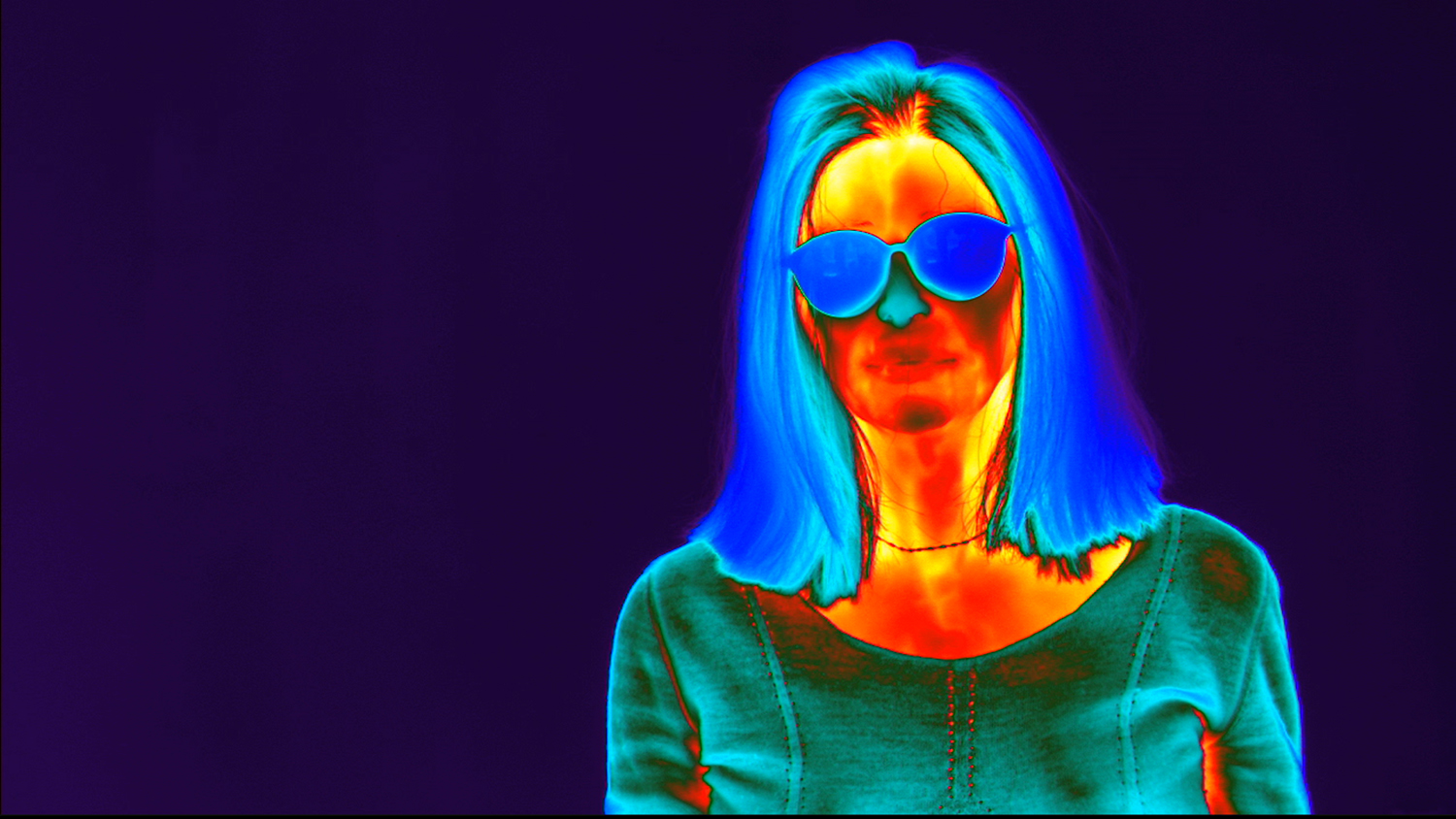

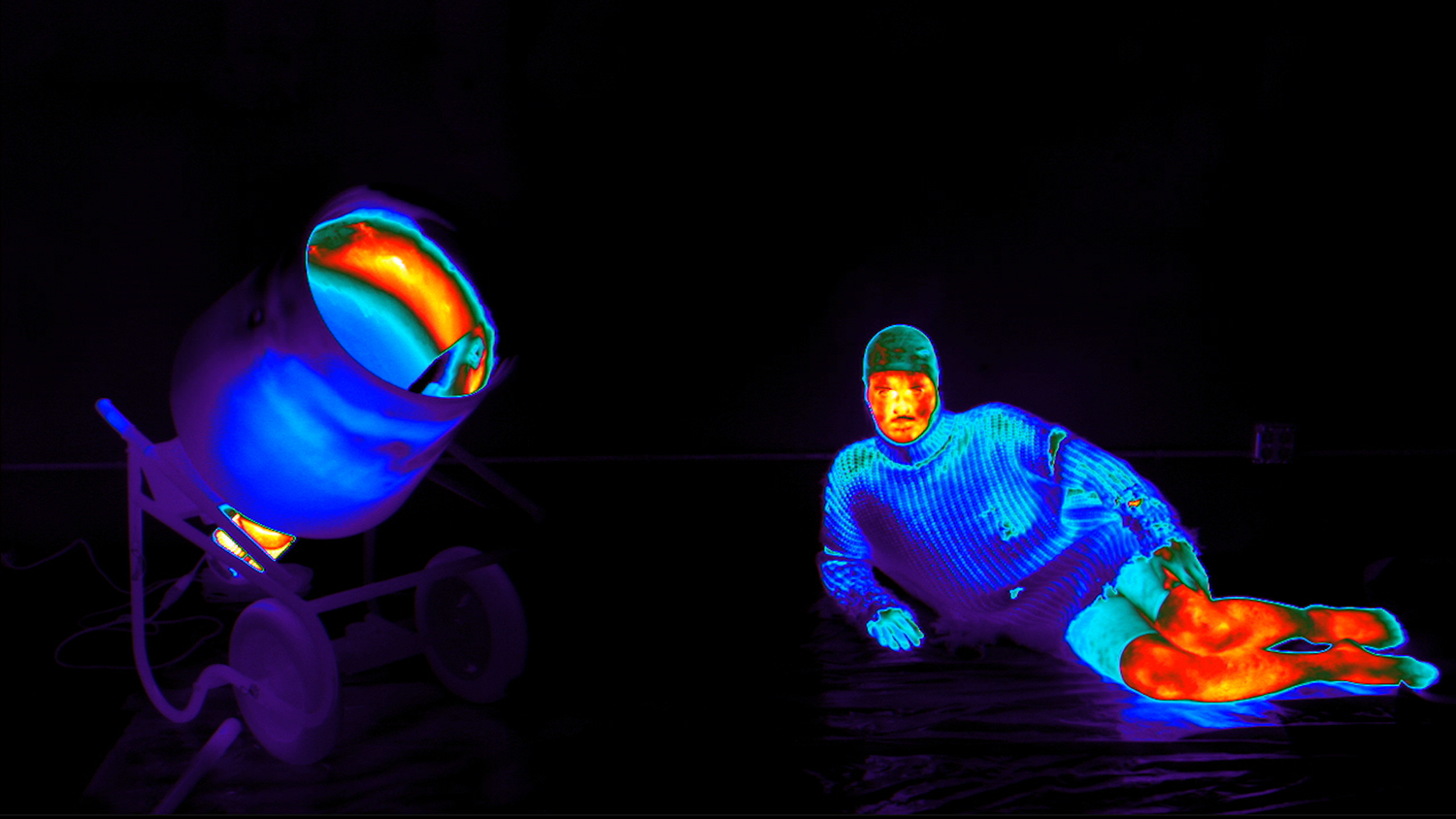

The monologue is intercut with comparatively otherworldly sequences. These include choreographic gestures shot with high-definition thermal imagery and performed primarily by Staff. The thermal scenes draw attention to the ways in which our ostensibly uniform bodies are actually composed of varying zones of heat and coolness, suggesting a visual analog for the complexity of identity. As the various temperatures of skin are registered in a radiant spectrum of colors, bodies looks simultaneously unsettling and mesmerizing, erotic and infected. At one point in the thermal footage, Staff is accompanied by a revolving cement mixer, which stands in as a prosthetic body, in a duet between human and machine, or the organic and the constructed.

Towards the end of the video, artist Jamie Crewe presents a passionate, lip-synched rendition of a love song in a gay bar. As Crewe ardently moves to the lyrics “to be in love with you is everything,” thwarted desire appears as a kind of intoxicating illness.³ This scene echoes a sequence from Claire Denis’s film I Can’t Sleep (1994) in which the protagonist (who later is revealed to be a reluctant murderer of old women) performs tenderly in drag to a roomful of dismissive men. In Staff’s reimagining of this scenario, Crewe attempts to fill, or infect, the room with a show of love and suffering. At the same time, she seems nearly invisible to the bar’s uninterested patrons, whose rejection she painfully ingests. Internal states and external appearances are blurred.

Each of the performers in Weed Killer identifies as transgender. By probing both cancer and trans experiences, Staff initiates a dialogue about how biomedical technologies have fundamentally transformed the social constitution of our bodies. The work builds on that of earlier artists—such as Jo Spence and General Idea, who in the 1980s tackled cancer and the AIDS crisis, respectively—which foregrounded how the treatment of illness and wellness are deeply political and social issues.⁴ Staff’s focus, however, is not on a single condition, but on the overlapping ways in which our bodies are transformed and regulated pharmacologically, from the use of chemotherapy and antidepressant drugs to hormone therapies. Simultaneously, Weed Killer draws attention to complex experiences of personal suffering in order to highlight the fine line between alternately poisonous and curative substances.

1 Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharma-copornagraphic Era, trans. Bruce Benderson (New York: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2013), 26–27.

2 “Evolution of Cancer Treatments: Chemotherapy,” American Cancer Society, accessed Jan 16, 2017, http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancerbasics/thehistoryofcancer/the-history-of-cancer-cancer-treatment-chemo.

3 The song was adapted by Staff from versions of the song To Be In Love (1999) by Masters at Work, featuring India.

4 Emblematic works include Jo Spence’s Cancer Shock (1982) and General Idea’s AIDS Wallpaper (1989).