Introducing: Jessi Reaves and Gaetano Pesce

A conversation between artist Jessi Reaves and artist, designer, and architect Gaetano Pesce. The dialogue took place in person at Pesce’s studio in Brooklyn, New York. This is the first time the two have spoken.

Gaetano Pesce: So how will we start, Marco?

Marco Kane Braunschweiler: For me, both of your work deals with the plasticity of form and a kind of anthropomorphism. In your case very overt and in Jessi’s case a bit more subtle. So I’m curious to discuss your approaches, I see them as a decomposition of material that’s then recomposed into iterative forms. I think of both of your work as an ontology—an ontological study of architecture and domestic objects—a study in what a building, a chair, a vase, can be.

Since we’re here in the studio I’m curious a bit about your process. Do you come to the studio early? Do you stay late? Is this typical?

GP: Not me, I came maybe half an hour ago. I work only in the morning. Then when I need to come here, I come here. Otherwise, I go to the office on Broadway. There we do what we call “clean work.” Like project drawings, relations with museums, exhibitions. That is the way I work when I am in New York, because fortunately or unfortunately, I travel a lot. Every month for a week, if it’s not more. And you, Jessi?

Jessi Reaves: I do the reverse, wake up and try to get to the studio as quickly as I can, I don’t do a lot of “clean work” or office work besides sending emails.

GP: So where do you have your office—your workplace?

JR: My studio is in Chelsea in the basement of an old carriage house. They used to keep horses down there.

GP: And you work alone there?

JR: I share the space with another artist. She’s there three days a week.

GP: But is there is someone helping you, or no?

JR: No, every once in awhile I have an assistant, but usually it’s just me alone down there.

GP: And can you do all this alone?

JR: For now I can do it alone. If I have trouble physically doing something alone, I’ll wait until my assistant can come. But I’ve gotten pretty good at moving things around, a four-by-eight sheet [of plywood]—I can swing that around by myself.

GP: Yeah, we have this problem too here. But we are…how many do we have here? We are four. And five with me, so…

JR: Have you always had people assisting you?

GP: I always work in the way I said. There is one office where they do a certain work and a workshop where we research and test material. Yesterday we did a test in something, and we didn’t succeed. So today I was thinking that we threw out a thousand dollars. Just like that, boom.

JR: Wow.

GP: Because, well—I don’t know why. So that happens, when you do research you never know where…you know where you start, but you don’t know if you’ll succeed.

JR: Right.

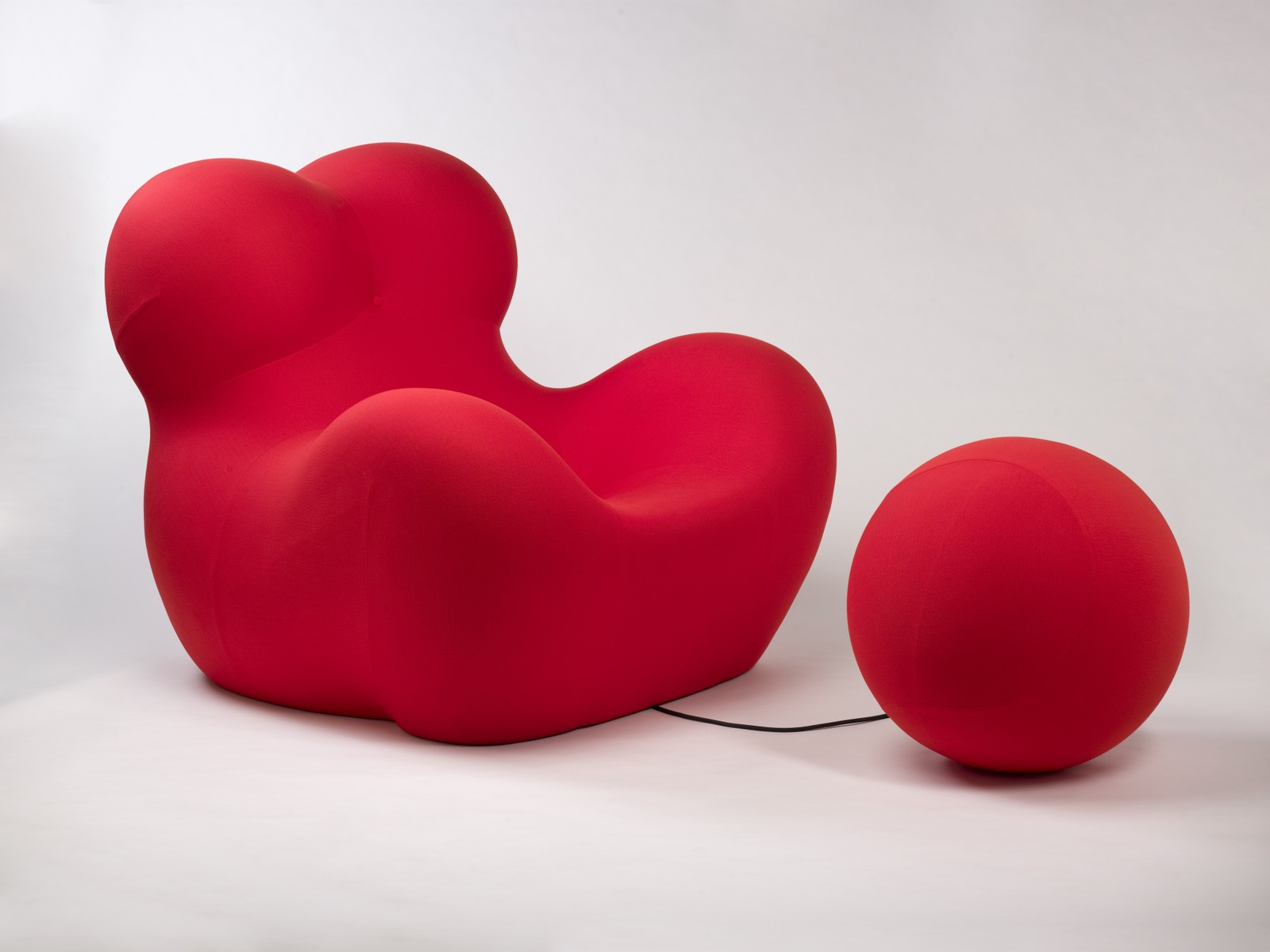

GAETANO PESCE, UP 5 LOUNGE CHAIR WITH UP 6 OTTOMAN , 1969, POLYURETHANE FOAM COVERED IN STRETCH FABRIC, (CHAIR): 40 X 43 1/2 X 45 INCHES (101.6 X 110.5 X 114.3 CM) (OTTOMAN): DIAM. 22 1/2 INCHES (57.2 CM)

GP: But Marco said something about the anthropomorphic image, that came to me not out of any kind of will but because when I was young, like you, I thought that the geometry that people were using at that time—and some are still using—was too abstract, too neutral, and I thought it was good to introduce a certain figure and images in general. The images at the beginning were parts of the human body. And for that time, now I talk about the year ’72, ’74, so it’s almost what? Forty-two, forty-four years ago? I realized that if you want to communicate with people, it’s good to use images because then they can understand what you do much better.

JR: Interesting.

GP: And so from human bodies to images, the step was very short.

JESSI REAVES, Rules Around Here (Waterproof Shelf), 2016 Plywood, vinyl, zippers, marker, 64 x 29 x 20 inches (162.56 x 73.66 x 50.80 cm), Courtesy Bridget Donahue, NYC

JR: I have a similar feeling about geometry in design. I’ve always felt there was this supposedly “scientific” approach to design that typically used geometry as a starting point. Like they were zooming in on nature and finding these tessellating patterns or molecular structures. And that justified their use of geometry somehow or made the geometry more intelligent—that type of interest in geometry feels so shallow. I don’t use images of bodies in the same way that you do, but I do tend to use organic shapes because they refer to the body automatically. So in that way you get a different type of image of nature than you do with hard geometry.

GP: The organic is already an image and is very strong if you compare it to a triangle, circle, or rectangular shape. The organic is much more rich.

JR: Right, because you see yourself.

GP: You can have more or less everything in the organic. They say that I use a lot of organic elements in my representations. But one interesting thing that is good to talk about today is…when I was twenty-four, such a long time ago, almost half a century, I started to think that the best freedom is the one from yourself. At that time the artist was expected to express a certain language and be recognizable through that language.

JR: Right—having a recognizable style.

GP: And I was saying, “No, that is not what I would like to do for myself.” Because we have the right to be incoherent. And why? It’s because time is incoherent. And if we follow time we cannot be always the same. Today I more or less follow that idea of incoherence. And usually I judge an artist—if it happens to be that I need to judge someone—through whether it’s recognizable or it’s not. Traditionally they start at the beginning and until the end of their life, they more or less they do the same thing. Time is a very serious partner. It changes all day, every day, every hour.

JR: You know it’s so interesting because lately, I’ve been thinking about that instinct to change. Something I admire when I look at other artists is whether the work has evolved or changed over time. But on the other hand, I know the feeling of obligation to see an idea or material experiment through—to stick with something until there’s really nothing left. It’s hard to know when you’ve gotten to a place with a certain idea, when it’s time to move on. I’m always afraid of not squeezing everything out of an idea or material, you know? Not seeing everything that’s there to be seen…

GP: You said material, material is incoherent. For example: one day someone discovers materials that are very heavy and very strong, and the day after someone else discovers another material that is completely different, very light and soft, but when you have it on your end you don’t feel it…

JR: But it seems like with your career you’ve found certain materials that you wouldn’t abandon even if something new came along. Like there’s something about that one material that lets you have versatility, and even if the material doesn’t change itself, there’s liquidity and space…

Installation view of Gaetano Pesce: Molds (Gelati Misti), September 3–November 27, 2016 at MOCA Pacific Design Center, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forrest

GP: If I discover myself working with materials that are liquid then I observe that the time in which I am living has liquid values.

JR: People ask me, “Will you always make furniture?” And it feels like such an irrelevant question because I feel like I’m following the ideas more than a particular form.

GP: When I saw this [pointing to an image of Reaves’ work], I thought it was interesting that someone like you—a young person called an artist—is interacting with furniture. Why? Furniture has a kind of magnetic force because it comes from production, and that is something that is very present in our life because everything comes from the production.

JR: That’s part of where the interest comes from. What you said before about time and values being liquid and coming in and out of style—I think production has been the same way. In the sixties and seventies, there was this idea that we would revert to the homemade, that the promises of production weren’t giving us everything we wanted from our objects or our lifestyle. I take a lot of inspiration from those periods where everyone had a craft hobby and people wanted to teach each other how to make their own furnishings. That failed, and now if a person is building their own bed that’s a very specialized skill. We don’t expect that from the average citizen at all.

GP: When you were explaining why you work with furniture I thought of how I came to what we call design. I discovered design because a woman who was staying with me, we were eighteen, nineteen years old, and she was studying sculpture, I was studying architecture. We were in a school in Venice, and one day she said, “You know they opened a new school called the industrial design school?” I didn’t know what that was, and then she said, “Do you want to come with me and go to this school?” And I said, “No, I am in the school of architecture.” So she became a student of this school and through her, I understood what design was, I realized that she was talking to me about a kind of art that was practical. And then years later I realized that art, what we call art, was always practical.

JESSI REAVES, Shelf for a Log, 2016 Plywood, sawdust, cane chair seat, ink, 34 x 68 x 13 inches (86.36 x 172.72 x 33.02 cm), Courtesy Bridget Donahue, NYC

JR: Right, but if something is functional it’s not always practical. Sometimes when I’m working I like to…to almost take all of the practicality out of an object and then try to put it back in. Even if the function isn’t as generous, there’s something else that’s happened.

GP: In your work, we have two dimensions, no? There is a chair and then there is something you add to that. A kind of second expression and the second expression is the culture of the object, no? The story of it, and that is why it is interesting…

JR: You’ve talked about liquidity and how it’s a metaphor for time. But I also think there’s a sense of making something permanent look like it happened very quickly, the idea of a pour…it just feels very fast…I know this wasn’t fast [pointing to an in-progress lamp] but it has that energy.

GP: At this certain moment in my life I understood that it was much better for me to allow the material to decide itself, and I could decide how to move, how to fix, how to cure. Because I understood it was much richer than what I was able to do.

JR: My experience with that is more in terms of being attached to the things in their imperfect state—when the upholstery on a piece of furniture has faded from sitting in the same place for years. It’s frustrating when people are so attached to perfection and to things looking new.

GP: Yeah, you said it—imperfection is super important.

JR: When you started working with plastic…there must have been a period of time where plastic was both innovative and exciting but also considered cheap? Or considered to be a lesser material than glass-ceramic? I feel that you elevate plastics to a place where it’s beyond those things. There was a time when…when it was both. It was exciting and new but also kind of trashy.

GP: There was a time when people were not buying my things because they were considering plastic something that was going to disappear. But slowly also museums now collect plastic objects.

JR: Of course!

GP: It’s not called plastic because that’s very negative, it’s called synthetic material. Some of the synthetic materials are better than the traditional material.

JR: I work with plywood because it’s the cheapest way to work with wood. You could call it “engineered wood.” It has fragility, it’s not pristine and durable like maple or walnut. And it changes, its color fades over time. I really like those qualities, and I like how you use synthetic materials for that same reason.

GP: Yeah, but the fade…a piece of wood, if it’s very old you see that it’s very dark.

JR: Yes, it gets darker brown as the light hits it. Or silver if it sits outside in the elements.

GP: But then if you sand it, it could become very light again. So everything changes as I said before. The aging process attacks everything—marble, stone, metal, everything. You mentioned glass…I work with glass. But compared to the synthetics I use, glass is a poor material.

JR: Right, I imagine working with synthetic materials you can change your mind, too, in a way you can’t with glass. I’m kind of intimidated by any material or process where I can’t change my mind in an instant.

JESSI REAVES, Foam Couch with Straps, 2016 Upholstery foam, fiberglass, wood, webbing, 29 x 77 x 35 inches (73.66 x 195.58 x 88.90 cm), Courtesy Bridget Donahue, NYC

GP: So I saw you work also with foam, no?

JR: Oh yes. You know, people always give me a hard time about its longevity. And I feel like people aren’t aware that there’s foam in everything, you know? We don’t show it naturally without a covering, without any fabric over it. People are so repulsed by it. But you’re always sitting on foam.

How do you choose your projects? Is it by the location or the feeling from the people who reach out to you?

GP: By curiosity. Usually, we work here following ideas or curiosities. And it’s very rare that we do something because someone asked. For instance, these chairs we are sitting on—we did them last year but we did them for ourselves and now maybe there is a company in Belgium that is interested to produce them. So it depends on ideas.

JR: I’m fortunate to have a schedule of projects coming up, but when I’m in the studio I’m trying to pretend there’s no deadline. And trying to do what you’re talking about, following ideas and making things for myself without thinking, “this has to be finished by this time.”

GP: We have deadlines more related to exhibitions but not deadlines for what we do. So there is no carrier work. It’s jumping from one subject to another.

JR: I can’t imagine having a creative practice that wouldn’t let you digest that way…like your mood could change…

GP: One day you read the paper and you have an idea, and the day after you see a movie and you had another idea. I am not recognizable. I am not doing a bottle, always the bottle, big bottle…

JR: [laughs] In one of the first studio visits I ever had someone asked me, “Do you want to have a recognizable style?” I was just so thrown by that question. It wasn’t something I had genuinely considered. It’s an idea from the outside that enters and once you hear it it’s hard to forget. Like, “Oh, a recognizable style?”

GP: In 1972, I did an exhibition with others at the Museum of Modern Art, it was a very famous exhibition called Italy: The New Domestic Landscape.

JR: Oh, yes. I have the book.

GP: And then, who approached me was a very famous gallerist, Leo Castelli. Leo Castelli said, “I would like to see your work.” At that time it was very close to the summer, and I was going to Venice. So he said, “I’ll come for the Biennale, and we will see each other in two months.”

We had an appointment in Piazza San Marco. I did not believe the guy was coming, I arrived late, and he was there waiting. We went to my atelier, and he was interested and said, “What I see—are you able to keep doing this all the time?” And I said, “No.” He explained to me, “If you change, I have to always do the work to make you recognizable.” He said, “I cannot work with someone who changes all the time.” I said, “Okay, I cannot promise to be always the same.”

This conversation was edited organized by Marco Kane Braunschweiler and edited by Karly Wildenhaus.